Leaving the post office, Leah Mirsky knows that she’s got to get out of the city. Get out of the country. She finds it hard to believe that she was so stupid as to think that Budapest could have been any sort of refuge. When she’d first arrived, fleeing the Bolshevik pogroms in Odessa, it had seemed liked a comforting piece of the old Empire, Gentiles and Jews of all nations living together, assimilated.

The war stripped all that illusion away. Now she sees behind the baroque pastry facades and knows that it’s the same as it ever was: everyone for themselves and kill the Jews first.

She takes very little comfort in the fact that she wasn’t completely stupid when she arrived. She used the skills that Binyamin, her older brother, had taught her. She’d gone to the right places, made the right connections, and gotten fake papers that gave her the identity of a Ukrainian Christian refugee.

So, hurrying down the street, dressed in worn men’s clothes with a hat pulled down low, heavy coat obscuring her shape, she does what everyone else does when they see someone with a yellow star sewn to their clothes. She looks away. She ignores them. She steps around them. She doesn’t let herself think about it. There are too many freight trains leaving the stations full and coming back empty. There are too many silent houses that once contained Jewish families.

She also does something else that everyone does. Every once and in a while, army vehicles go past on the street, heading to the Eastern Front. The people, including Leah, stop and cheer them as they go past. She’s got no love for the Russians, more reasons than most to hate them, but she takes a small piece of comfort from the fact that those trucks are also going away full and coming back empty. Rumors are that something bad is happening around Stalingrad.

But all of this, all these thoughts, all these actions are performed automatically. Leah’s mind is on what she has to do next, the next steps in the plan. She knows that there’s a better than even chance that she’ll end up having to spread her legs for that bastard, but the gun in her pocket is a comforting weight. She walks fast, head down, doing all she can to not draw attention to herself, sticking to the building side of the sidewalk.

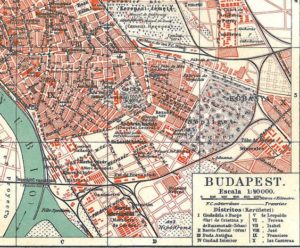

Quickly, she heads away from the main streets, away from the Danube, and makes her way into a shabbier section of the city. The Ostbanhof, the train station for the east, is nearby, which was a major factor in her choosing this particular piece of shit for her plan.

Razinsky’s a Pole, clawed himself a piece of the sex and smut trade. Fancies himself a decadent man about the town, hair slicked back, pencil mustache, cigarette in a holder. Even beneath the awful cologne, he stinks. She can smell him from across the room. His eyes are small, greedy, stupid.

His office, one evening, in a cafe, when she was looking for the right target, Leah heard him refer to it as his studio, is a large room. One corner is set up with a tattered velvet couch, Leah doesn’t even bother thinking about the stains on it. His desk, a baroque Austro-Hungarian monstrosity, carved with trees and animal feet and heraldic signs, Leah wouldn’t be surprised if there was a working cuckoo clock hiding somewhere among all that, the desk is facing the door on the opposite side of the room. She sits, huddled in her coat, hat in her lap, in front of that awful desk. She doesn’t look directly at him, keeps her gaze on the carvings. The gun digs into her back.

Razinsky, behind his desk, leans back in his chair, gestures towards her with his cigarette holder. “Why the men’s clothes? Trying for some sort of Marlene Dietrich thing?” He shrugs. “If you want to do specialty acts, I can arrange that, sure. But for now, get them off. I want to see the merchandise.”

Leah stands and shrugs off her coat. She knows what she has to do. She knows that she will do it. But her fingers tremble, just a little, as she starts to undo the buttons on her shirt. She’s ashamed and angry at her shame. She’s angry at the world for going mad and destroying her life and dreams and family. And she’s very angry at the greasy pimp leering at her from across his desk.

Then Razinsky opens his mouth and makes everything easier. He spots the trembling fingers. “A virgin? I can’t fucking believe it. I knew there was a reason that I got out of bed this morning.” He shoves back his chair and gets to his feet. His attention is completely on her breasts as they are revealed by her parting shirt.

He doesn’t even have time to change expression before she shoots him in the head. The sound is surprisingly loud for such a small gun, louder than she thought it would be. . Razinsky drops to the floor behind the desk. The beginning of an expression of stupid shock frozen on his face. Just another man who underestimated her. She deliberately doesn’t think of her father.

Leah stands there for a few seconds, head cocked, listening, but there doesn’t seem to be anyone coming to investigate. She shoves the gun back into a pocket and moves quick. Rings, wallet, money clip, she removes those from Razinsky’s body. The desk provides another roll of bills. She pauses and considers the gun in the upper drawer. Then she shakes her head. One gun is enough. She’s not Benny, she’s planning on getting by with as little shooting as possible.

Her fingers start trembling. She can’t make the money clip with its bills fit into her pocket. The pinky ring makes a sounds that she can barely hear through echoes in her ears when it falls onto the desk top. She stops. Stands there next to the dead man cooling on the floor. Closes her eyes for a moments. Doesn’t breathe too deep to avoid the reek of Razinsky. The smells are bad: his cologne mixed with the sulphurous gunpowder mixed with shit from where his bowels released in death. The smell coats the back of her mouth and she gags briefly. She presses the back of her hand to her mouth and nose until her stomach stops churning. Rests her fingers on the top of the desk to still their trembling.

She wants to be tough, tough like Benny, memories of him back in Odessa, him and his gang standing up to the Cossacks, to the Russian who thought Jews were just easy meat for beatings. The stories that went around the Jewish community, of him and his gang. Wants to be as tough as he is but she’s not.

When she sees him next, she’s going tell him what a pain in the neck he is, him and his gangster reputation, the impossibility of living up to that. She shakes her head, driving away thoughts of the future. She knows that thinking of anything past the next hour is a luxurious stupidity that she can’t afford. She opens her eyes and gets moving.

The Ostbanhof is chaos. Which is exactly what Leah was hoping for. This time of day, late afternoon, all the small merchants and peasants who have come into the city for a day of business are heading home. Finally, the old man in front of her at the ticket sellers window finishes counting out his small change and pushes it across the counter to the agent. Then he takes several minutes to carefully look at the ticket and ask the seller several questions. By this time, Leah’s grinding her teeth so hard, she can hear them over the clamor of the train station. Eventually, an eternity later, he totters away, his ticket grasped in one gnarled fist. Leah takes one last look around the station to make sure that no one is paying any extra attention to her or making a search of the station. Nobody except the rest of the people in the line who wish that she’d hurry up and buy her ticket.

“Round trip to Debrechen. Third class.” She keeps her voice pitched low and her hat pulled down over her eyes. She doesn’t look at the seller and is glad that she thought to wear gloves. Her hands would have given her away as a woman. She doesn’t know when people will be looking for her, but she does know that they will be. Gangsters, Nazis, Hungarian fascists, no difference, really, between them, but she’s a Jew on the run who just killed and robbed a pimp. That makes her fair game for all of them. If they track her this far, her destination will throw them off the track. Cegled is on the way to Debrechen. When she gets there, she’ll change trains, probably dressed as a woman to further muddy the waters, and head south, towards the Carpathian Mountains on the Hungarian/Romanian border. Or maybe Serbia, catch the Danube and try to get passage through to Bulgaria and Varna on the Black Sea. Again, she keeps her mind on the next step. Get on the train. Find a seat. She doesn’t think about what rumor says lives in the Carpathians.

“10 forints.” The ticket seller barely looks at her, attention stays on getting the ticket as she hands the money over. No wonder the old man left counting his change, this is over three times the usual rate. But war time means war time rates. She takes the ticket and heads to her train, moving through the crowds towards the sound and steam of the engines..

She dodges around a large family, the mother and father trying to keep the five children all together, she can see the platform she wants, and almost runs directly into a militiaman.

“Papers and ticket.” His voice is a bored monotone overlaid with the satisfaction that comes from having power over people.

She’s prepared for this, but she can’t help, just for an instance, can’t help thinking of the gun in her other pocket. Can’t help thinking of how good it would feel to shoot this bastard right in his fat pig face. But it’s just for an instant. Instead, from the inside coat pocket she pulls out the cheap fake papers that she’d bought from the forger six months ago when she started to wear mens’ clothes more and more frequently. They show her as a young clerk from eastern Hungary, up on the Ukrainian border. The papers aren’t of a very good quality, she didn’t have the money for quality, then. But the wad of money she’s folded underneath the papers makes up for the badly drawn stamps.

The first skill that all police learn is how to make bribes disappear quickly. This one demonstrates his skill as the folded bills vanish in the blink of an eye. He doesn’t speak, just grunts and waves her away. She nods subserviently and hurries to the line of train cars.

Leah’s one of the last on board, pushing her way up the steps as the train begins to move out of the station. All the cars are crowded, packed tight, and she ends up standing on the platform between cars, swaying in the motion of the train, clutching Crying? But not the only one.